1.4. The Command Line¶

The command line is a text-based program that lets you enter commands to interact with the operating system and run programs. You might also hear it called the command line interface (CLI, which rhymes with “fly”), com- mand prompt, terminal, shell, or console. It provides an alternative to a graphical user interface (GUI, pronounced “gooey”), which allows the user to interact with the computer through more than just a text-based interface. A GUI presents visual information to a user to guide them through tasks more easily than the command line does. Most computer users treat the command line as an advanced feature and never touch it. Part of the intimi- dation factor is due to the complete lack of hints of how to use it; although a GUI might display a button showing you where to click, a blank terminal window doesn’t remind you what to type.

But there are good reasons for becoming adept at using the com- mand line. For one, setting up your environment often requires you to use the command line rather than the graphical windows. For another, enter- ing commands can be much faster than clicking graphical windows with the mouse. Text-based commands are also less ambiguous than dragging an icon to some other icon. This lends them to automation better, because you can combine multiple specific commands into scripts to perform sophisticated operations.

The command line program exists in an executable file on your com- puter. In this context, we often call it a shell or shell program. Running the shell program makes the terminal window appear:

On Windows, the shell program is at C::raw-latex:`\Windows`:raw-latex:`\System32`:raw-latex:`\cmd`.exe.

On macOS, the shell program is at /bin/bash.

On Ubuntu Linux, the shell program is at /bin/bash.

Over the years, programmers have created many shell programs for the Unix operating system, such as the Bourne Shell (in an executable file named sh) and later the Bourne-Again Shell (in an executable file named Bash). Linux uses Bash by default, whereas macOS uses the similar Zsh or Z shell in Catalina and later versions. Due to its different develop- ment history, Windows uses a shell named Command Prompt. All these programs do the same thing: they present a terminal window with a text- based CLI into which the user enters commands and runs programs.

In this section, you’ll learn some of the command line’s general concepts and common commands. You could master a large number of cryptic com- mands to become a real sorcerer, but you only need to know about a dozen or so to solve most problems. The exact command names might vary slightly on different operating systems, but the underlying concepts are the same.

1.4.1. Opening a Terminal Window¶

To open a terminal window, do the following:

On Windows, click the Start button, type Command Prompt , and then pressENTER.

On macOS, click the Spotlight icon in the upper-right corner, typeTerminal , and then press ENTER.

On Ubuntu Linux, press the WIN key to bring up Dash, type Terminal ,and press ENTER. Alternatively, use the keyboard shortcut CTRL-ALT-T.

Like the interactive shell, which displays a >>> prompt, the terminal displays a shell prompt at which you can enter commands. On Windows, the prompt will be the full path to the current folder you are in:

C:UsersAl>your commands go here

On macOS, the prompt shows your computer’s name, a colon, and the cwd with your home folder represented as a tilde ( ~ ). After this is your user- name followed by a dollar sign ( $ ):

Als-MacBook-Pro:~ al$ your commands go here

On Ubuntu Linux, the prompt is similar to the macOS prompt except it begins with the username and an at ( @ ) symbol:

al@al-VirtualBox:~$ your commands go here

Many books and tutorials represent the command line prompt as just $to simplify their examples. It’s possible to customize these prompts, but doing so is beyond the scope of this book.

1.4.2. Running Programs from the Command Line¶

To run a program or command, enter its name into the command line. Let’s run the default calculator program that comes with the operating system. Enter the following into the command line:

On Windows, enter calc.exe .

On macOS, enter open -a Calculator . (Technically, this runs the open program, which then runs the Calculator program.)

On Linux, enter gnome-calculator .

Program names and commands are case sensitive on Linux but case insensitive on Windows and macOS. This means that even though you must type gnome-calculator on Linux, you could type Calc.exe on Windows and OPEN –a Calculator on macOS.

Entering these calculator program names into the command line is equivalent to running the Calculator program from the Start menu, Finder, or Dash. These calculator program names work as commands because the calc.exe, open, and gnome-calculator programs exist in folders that are included in the PATH environment variables. “Environment Variables and PATH” on page 35 explains this further. But suffice it to say that when you enter a program name on the command line, the shell checks whether a program with that name exists in one of the folders listed in PATH . On Windows, the shell looks for the program in the cwd (which you can see in the prompt) before checking the folders in PATH . To tell the command line on macOS and Linux to first check the cwd, you must enter ./ before the filename.

If the program isn’t in a folder listed in PATH , you have two options:

Use the cd command to change the cwd to the folder that contains the program, and then enter the program name. For example, you could enter the following two commands:

cd C:WindowsSystem32 calc.exe

Enter the full file path for the executable program file. For example,instead of entering calc.exe , you could enter C::raw-latex:`\Windows`:raw-latex:`\System32`:raw-latex:`\calc`.exe .

On Windows, if a program ends with the file extension .exe or .bat, including the extension is optional: entering calc does the same thing as entering calc.exe . Executable programs in macOS and Linux often don’t have file extensions marking them as executable; rather, they have the exe- cutable permission set. “Running Python Programs Without the Command Line” on page 39 has more information.

1.4.3. Using Command Line Arguments¶

Command line arguments are bits of text you enter after the command name. Like the arguments passed to a Python function call, they provide the com- mand with specific options or additional directions. For example, when you run the command cd C::raw-latex:`\Users `, the C::raw-latex:`Users `part is an argument to the cd command that tells cd to which folder to change the cwd. Or, when you run a Python script from a terminal window with the python yourScript.py com- mand, the yourScript.py part is an argument telling the python program what file to look in for the instructions it should carry out.

Command line options (also called flags, switches, or simply options) are a single-letter or short-word command line arguments. On Windows, com- mand line options often begin with a forward slash ( / ); on macOS and Linux, they begin with a single dash ( – ) or double dash ( – ). You already used the –a option when running the macOS command open –a Calculator . Command line options are often case sensitive on macOS and Linux but are case insensitive on Windows, and we separate multiple command line options with spaces.

Folders and filenames are common command line arguments. If the folder or filename has a space as part of its name, enclose the name in dou- ble quotes to avoid confusing the command line. For example, if you want to change directories to a folder called Vacation Photos, entering cd Vacation Photos would make the command line think you were passing two argu- ments, Vacation and Photos . Instead, you enter cd “Vacation Photos” :

C:UsersAl>cd "Vacation Photos" C:UsersAlVacation Photos>

Another common argument for many commands is –help on macOS and Linux and /? on Windows. These bring up information associated with the command. For example, if you run cd /? on Windows, the shell tells you what the cd command does and lists other command line arguments for it:

C:UsersAl>cd /? Displays the name of or changes the current directory. CHDIR [/D] [drive:][path] CHDIR [..] CD [/D] [drive:][path] CD [..] .. Specifies that you want to change to the parent directory. Type CD drive: to display the current directory in the specified drive. Type CD without parameters to display the current drive and directory. Use the /D switch to change current drive in addition to changing current directory for a drive. --snip—

This help information tells us that the Windows cd command also goes by the name chdir . (Most people won’t type chdir when the shorter cd com- mand does the same thing.) The square brackets contain optional argu- ments. For example, CD [/D] [drive:][path] tells you that you could specify a drive or path using the /D option.

Unfortunately, although the /? and –help information for commands provides reminders for experienced users, the explanations can often be cryptic. They’re not good resources for beginners. You’re better off using a book or web tutorial instead, such as The Linux Command Line, 2nd Edition (2019) by William Shotts, Linux Basics for Hackers (2018) by OccupyTheWeb, or PowerShell for Sysadmins (2020) by Adam Bertram, all from No Starch Press. ## Running Python Code from the Command Line with -c If you need to run a small amount of throwaway Python code that you run once and then discard, pass the –c switch to python.exe on Windows or python3 on macOS and Linux. The code to run should come after the –c switch, enclosed in double quotes. For example, enter the following into the terminal window:

C:UsersAl>python -c "print('Hello, world')" Hello, world

The –c switch is handy when you want to see the results of a single Python instruction and don’t want to waste time entering the interactive shell. For example, you could quickly display the output of the help() func- tion and then return to the command line:

C:UsersAl>python -c "help(len)" Help on built-in function len in module builtins: len(obj, /) Return the number of items in a container. C:UsersAl>

1.4.4. Running Python Programs from the Command Line¶

Python programs are text files that have the .py file extension. They’re not executable files; rather, the Python interpreter reads these files and carries out the Python instructions in them. On Windows, the interpreter’s execut- able file is python.exe. On macOS and Linux, it’s python3 (the original python file contains the Python version 2 interpreter). Running the commands python yourScript.py or python3 yourScript.py will run the Python instruc- tions saved in a file named yourScript.py. ## Running the py.exe Program On Windows, Python installs a py.exe program in the C::raw-latex:`\Windows `folder. This program is identical to python.exe but accepts an additional command line argument that lets you run any Python version installed on your computer. You can run the py command from any folder, because the C::raw-latex:`Windows `folder is included in the PATH environment variable. If you have multiple Python versions installed, running py automatically runs the latest version installed on your computer. You can also pass a -3 or -2 command line argument to run the latest Python version 3 or version 2 installed, respectively. Or you could enter a more specific version number, such as -3.6 or -2.7 , to run that particular Python installation. After the version switch, you can pass all the same command line arguments to py.exe as you do to python.exe. Run the fol- lowing from the Windows command line:

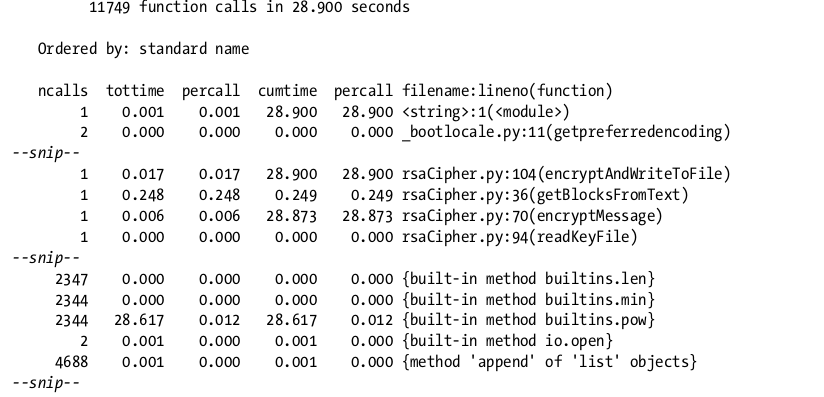

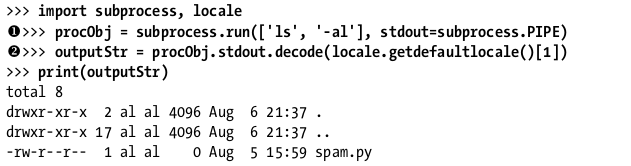

The py.exe program is helpful when you have multiple Python versions installed on your Windows machine and need to run a specific version. ## Running Commands from a Python Program Python’s subprocess.run() function, found in the subprocess module, can run shell commands within your Python program and then present the com- mand output as a string. For example, the following code runs the ls –al command:

We pass the [‘ls’, ‘-al’] list to subprocess.run() . This list contains the command name ls , followed by its arguments, as individual strings. Note that passing [‘ls –al’] wouldn’t work. We store the command’s output as a string in outputStr . Online documentation for subprocess.run() and locale. getdefaultlocale() will give you a better idea of how these functions work, but they make the code work on any operating system running Python. ## Minimizing Typing with Tab Completion Because advanced users enter commands into computers for hours a day, modern command lines offer features to minimize the amount of ty ping necessary. The tab completion feature (also called command line completion or autocomplete) lets a user type the first few characters of a folder or filename and then press the TAB key to have the shell fill in the rest of the name.

For example, when you type cd c::raw-latex:`\u a`nd press TAB on Windows, the current command checks which folders or files in C: begin with u and tab completes to c::raw-latex:`Users . It corrects the lowercase u to U as well. (On macOS and Linux, tab completion doesn’t correct the casing.) If multiple folders or filenames begin with U in the C: folder, you can continue to press TAB to cycle through all of them. To narrow down the number of matches, you could also type cd c::raw-latex:us `, which filters the possibilities to folders and file- names that begin with us.

Pressing the TAB key multiple times works on macOS and Linux as well. In the following example, the user typed cd D , followed by TAB twice:

al@al-VirtualBox:~$ cd D Desktop/ Documents/ Downloads/ al@al-VirtualBox:~$ cd D

Pressing TAB twice after typing the D causes the shell to display all the possible matches. The shell gives you a new prompt with the command as you’ve typed it so far. At this point, you could type, say, e and then press TAB to have the shell complete the cd Desktop/ command.

Tab completion is so useful that many GUI IDEs and text editors include this feature as well. Unlike command lines, these GUI programs usually display a small menu under your words as you type them, letting you select one to autocomplete the rest of the command. ## Viewing the Command History In their command history, modern shells also remember the commands you’ve entered. Pressing the up arrow key in the terminal fills the command line with the last command you entered. You can continue to press the up arrow key to find earlier commands, or press the down arrow key to return to more recent commands. If you want to cancel the command currently in the prompt and start from a fresh prompt, press CTRL-C.

On Windows, you can view the command history by running doskey /history . (The oddly named doskey program goes back to Microsoft’s pre- Windows operating system, MS-DOS.) On macOS and Linux, you can view the command history by running the history command. ## Working with Common Commands This section contains a short list of the common commands you’ll use in the command line. There are far more commands and arguments than listed here, but you can treat these as the bare minimum you’ll need to navigate the command line.

Command line arguments for the commands in this section appear between square brackets. For example, cd [destination folder] means you should enter cd , followed by the name of a new folder. ### Match Folder and Filenames with Wildcard Characters Many commands accept folder and filenames as command line arguments. Often, these commands also accept names with the wildcard characters and? , allowing you to specify multiple matching files. Thecharacter matches any number of characters, whereas the ? character matches any single character. We call expressions that use the * and ? wildcard charac- ters glob patterns (short for “global patterns”).

Glob patterns let you specify patterns of filenames. For example, you could run the dir or ls command to display all the files and folders in the cwd. But if you wanted to see just the Python files, dir .py or ls.py would display only the files that end in .py. The glob pattern *.py means “any group of characters, followed by .py”:

The glob pattern records201?.txt means “ records201 , followed by any sin- gle character, followed by .txt .” This would match record files for the years records2010.txt to records2019.txt (as well as filenames, such as records201X.txt). The glob pattern records20??.txt would match any two characters, such as records2021.txt or records20AB.txt. ### Change Directories with cd Running cd [destination folder] changes the shell’s cwd to the destination folder:

C:UsersAl>cd Desktop C:UsersAlDesktop>

The shell displays the cwd as part of its prompt, and any folders or files used in commands will be interpreted relative to this directory.

If the folder has spaces in its name, enclose the name in double quotes. To change the cwd to the user’s home folder, enter cd ~ on macOS and Linux, and cd %USERPROFILE% on Windows.

On Windows, if you also want to change the current drive, you’ll first need to enter the drive name as a separate command:

C:UsersAl>d: D:>cd BackupFiles D:BackupFiles>

To change to the parent directory of the cwd, use the .. folder name:

C:UsersAl>cd .. C:Users>

List Folder Contents with dir and ls¶

On Windows, the dir command displays the folders and files in the cwd. The ls command does the same thing on macOS and Linux. You can dis- play the contents of another folder by running dir [another folder] or ls [another folder] .

The -l and -a switches are useful arguments for the ls command. By default, ls displays only the names of files and folders. To display a long list- ing format that includes file size, permissions, last modification timestamps, and other information, use –l . By convention, the macOS and Linux oper- ating systems treat files beginning with a period as configuration files and keep them hidden from normal commands. You can use -a to make ls dis- play all files, including hidden ones. To display both the long listing format and all files, combine the switches as ls -al . Here’s an example in a macOS or Linux terminal window:

The Windows analog to ls –al is the dir command. Here’s an example in a Windows terminal window:

List Subfolder Contents with dir /s and find¶

The find . –name command does the same thing on macOS and Linux:

al@ubuntu:~/Desktop$ find . -name "*.py" ./someSubFolder/eggs.py ./someSubFolder/bacon.py ./spam.py

The . tells find to start searching in the cwd. The –name option tells find to find folders and filenames by name. The “.py” tells find to display folders and files with names that match the.py pattern. Note that the find com- mand requires the argument after –name to be enclosed in double quotes. ### Copy Files and Folders with copy and cp To create a duplicate of a file or folder in a different directory, run copy [source file or folder] [destination folder] or cp [source file or folder] [destination folder] . Here’s an example in a Linux terminal window:

al@ubuntu:~/someFolder$ ls hello.py someSubFolder al@ubuntu:~/someFolder$ cp hello.py someSubFolder al@ubuntu:~/someFolder$ cd someSubFolder al@ubuntu:~/someFolder/someSubFolder$ ls hello.py

SHOR T COMM A ND N A ME S

When I started learning the Linux operating system, I was surprised to find that the Windows copy command I knew well was named cp on Linux. The name “copy” was much more readable than “cp.” Was a terse, cryptic name really worth saving two characters’ worth of typing?

As I gained more experienced in the command line, I realized the answer is a firm “yes.” We read source code more often than we write it, so using ver- bose names for variables and functions helps. But we type commands into the command line more often than we read them, so in this case, the opposite is true: short command names make the command line easier to use and reduce strain on your wrists.

Move Files and Folders with move and mv¶

On Windows, you can move a source file or folder to a destination folder by running move [source file or folder] [destination folder] . The mv [source file or folder] [destination folder] command does the same thing on macOS and Linux.

Here’s an example in a Linux terminal window:

al@ubuntu:~/someFolder$ ls hello.py someSubFolder al@ubuntu:~/someFolder$ mv hello.py someSubFolder al@ubuntu:~/someFolder$ ls someSubFolder al@ubuntu:~/someFolder$ cd someSubFolder/ al@ubuntu:~/someFolder/someSubFolder$ ls hello.py

The hello.py file has moved from ~/someFolder to ~/someFolder/someSubFolder and no longer appears in its original location. ### Rename Files and Folders with ren and mv Running ren [file or folder] [new name] renames the file or folder on Windows, and mv [file or folder] [new name] does so on macOS and Linux. Note that you can use the mv command on macOS and Linux for moving and renaming a file. If you supply the name of an existing folder for the second argument, the mv command moves the file or folder there. If you supply a name that doesn’t match an existing file or folder, the mv command renames the file or folder. Here’s an example in a Linux terminal window: al@ubuntu:~/someFolder$ ls hello.py someSubFolder

al@ubuntu:~/someFolder$ mv hello.py goodbye.py al@ubuntu:~/someFolder$ ls goodbye.py someSubFolder

The hello.py file now has the name goodbye.py. ### Delete Files and Folders with del and rm To delete a file or folder on Windows, run del [file or folder] . To do so on macOS and Linux, run rm [file] ( rm is short for, remove).

These two delete commands have some slight differences. On Windows, running del on a folder deletes all of its files, but not its subfolders. The del command also won’t delete the source folder; you must do so with the rd or rmdir commands, which I’ll explain in “Delete Folders with rd and rmdir” on page 34. Additionally, running del [folder] won’t delete any files inside the subfolders of the source folder. You can delete the files by run- ning del /s /q [folder] . The /s runs the del command on the subfolders, and the /q essentially means “be quiet and don’t ask me for confirmation.” Figure 2-4 illustrates this difference.

Figure 2-4: The files are deleted in these example folders when you run del delicious (left) or del /s /q delicious (right).

On macOS and Linux, you can’t use the rm command to delete folders. But you can run rm –r [folder] to delete a folder and all of its contents. On Windows, rd /s /q [folder] will do the same thing. Figure 2-5 illustrates this task.

Figure 2-5: The files are deleted in these example folderswhen you run rd /s /q delicious or rm –r delicious .

Make Folders with md and mkdir¶

Running md [new folder] creates a new, empty folder on Windows, and run- ning mkdir [new folder] does so on macOS and Linux. The mkdir command also works on Windows, but md is easier to type.

Here’s an example in a Linux terminal window:

al@ubuntu:~/Desktop$ mkdir yourScripts al@ubuntu:~/Desktop$ cd yourScripts al@ubuntu:~/Desktop/yourScripts$ ls al@ubuntu:~/Desktop/yourScripts$

Notice that the newly created yourScripts folder is empty; nothing appears when we run the ls command to list the folder’s contents . ### Delete Folders with rd and rmdir Running rd [source folder] deletes the source folder on Windows, and rmdir [source folder] deletes the source folder on macOS and Linux. Like mkdir , the rmdir command also works on Windows, but rd is easier to type. The folder must be empty before you can remove it.

Here’s an example in a Linux terminal window:

al@ubuntu:~/Desktop$ mkdir yourScripts al@ubuntu:~/Desktop$ ls yourScripts

al@ubuntu:~/Desktop$ rmdir yourScripts al@ubuntu:~/Desktop$ ls al@ubuntu:~/Desktop$

In this example, we created an empty folder named yourScripts and then removed it.

To delete nonempty folders (along with all the folders and files it con- tains), run rd /s/q [source folder] on Windows or rm –rf [source folder] on macOS and Linux. ### Find Programs with where and which Running where [program] on Windows or which [program] on macOS and Linux tells you the exact location of the program. When you enter a com- mand on the command line, your computer checks for the program in the folders listed in the PATH environment variable (although Windows checks the cwd first).

These commands can tell you which executable Python program is run when you enter python in the shell. If you have multiple Python versions installed, your computer might have several executable programs of the same name. The one that is run depends on the order of folders in your PATH envi- ronment variable, and the where and which commands will output it:

C:UsersAl>where python C:UsersAlAppDataLocalProgramsPythonPython38python.exe